I Once Was Lost

In December, community members reported that a horse had been lost in Joshua Tree National Park. Something spooked Rupert while his owner prepared for a trail ride near (appropriately enough) Stirrup Tank Road, and he broke his bridle and cantered off.

Rupert’s predicament got me thinking both that the Year of the Horse is almost upon us and that the park has a history of lost horses.

In the Chinese zodiac, the horse stands for vitality, bold ideas, and success through effort. It’s a year said to favor those who take on challenges with courage and heart, which we could all use right now. The shadow side of this energy is restlessness, impulsivity, and volatility. Sounds like Rupert.

Johnny Lang and the Case of the Missing Horse

No horse story in Joshua Tree is complete without Johnny Lang and the Lost Horse Mine. Depending on who tells it, Lang either lost a horse, had it stolen, or followed it straight to the gold in them thar hills.

In one version, Lang sat down to fix his boot while searching for his wandering horse and spotted gold in the rock beneath him. In another, cattle rustlers known as the McHaney brothers took his horse at gunpoint. Either way, the mine that followed was named Lost Horse—and it eventually became the most productive mine in the area.

Gold poured out, but time and the desert took their toll. In his old age, Lang ran out of supplies. One by one, he ate his burros to survive. In 1925, he left a note on his cabin door:

“Gone for grub. Be back soon.”

He never returned.1

Heading into the 2026 elections, Desert Trumpet has sustained a potential 50% cut in funding. Help us provide the coverage you’ve come to expect by becoming a paid subscriber or upgrading your paid subscription today!

Burros on the Loose

Horses and burros are not native to the desert or even North America, and feral equines can be very destructive to the environment. There are small herds of feral burros in Death Valley National Park and the Mojave Preserve, and although they damage vegetation and water sources, they are protected under the 1971 Wild Free-Roaming Horses and Burros Act, which makes it illegal to harass or remove them without authorization. There are no feral burros in Joshua Tree National Park, although a hiking friend tells me that in the 1970s, a few escaped from a corral and roamed parts of the park for years before being captured.

Another friend I explore with said she’d heard stories about prospectors traveling the desert at night with their burros. It is said that to protect themselves from rattlesnakes hunting in the dark, some miners wrapped tin from coffee cans around their legs. If a rattlesnake struck, the makeshift shin guards might stop the fangs. I imagine a warm desert night, the burros walking, hooves crunching on soft sand, nickering and blowing dust from their nostrils, along with the weird metallic rattle of a prospector stomping along under the stars.

Yes, Horses Once Thrived Here

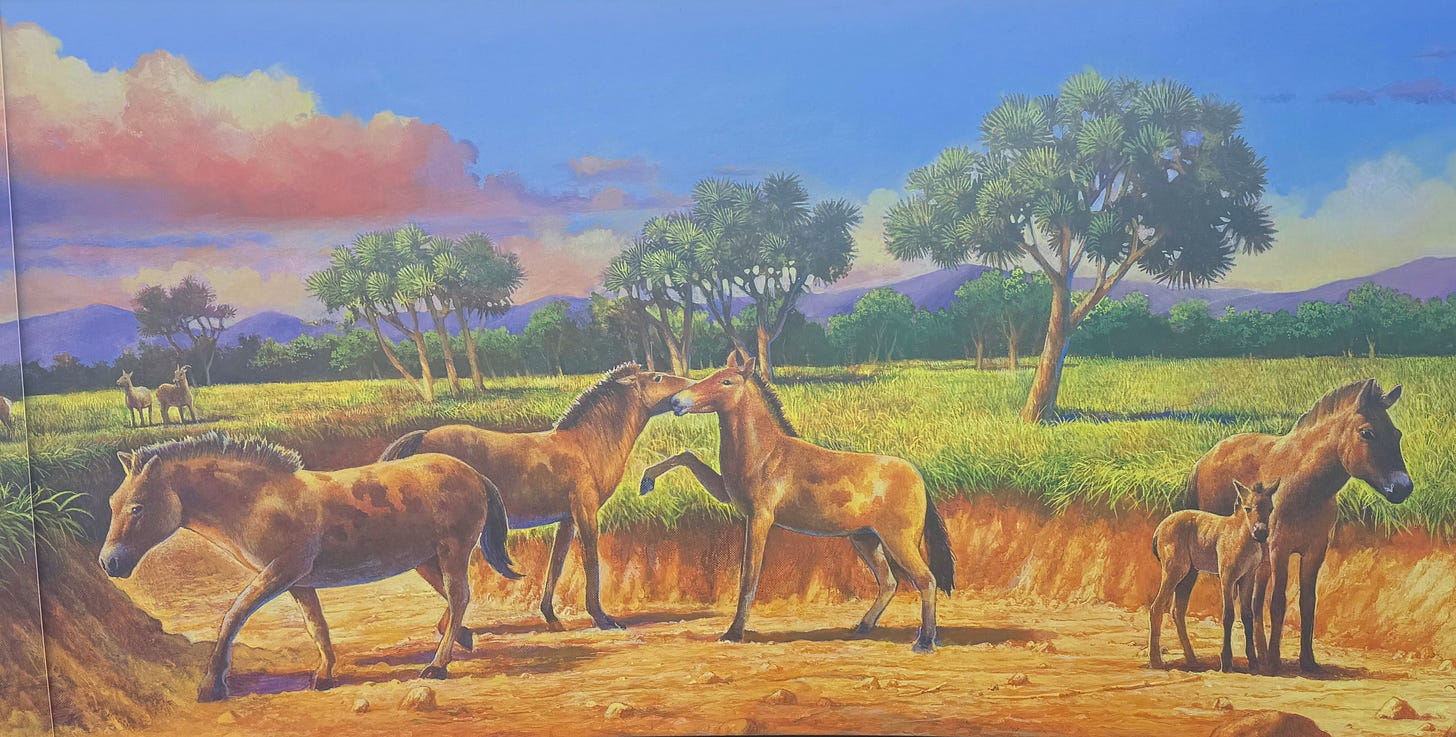

Horses evolved in North America millions of years ago, and fossils found in remoter parts of the park show that extinct species of wild horses lived here long ago.

These were not saddle horses but sturdy wild grazers sharing the land with mammoths, camels, bison, giant ground sloths, and saber-toothed cats. When it was so foggy on New Year’s Day, I looked out the window and wondered what it would be like to see these beasts drifting past. I wish we had a little more of that charismatic megafauna around.

During the last Ice Age, however, climates shifted, grasslands changed, and humans arrived, and it’s thought that most of the continent’s large mammals might have been hunted to extinction. By about 10,000 years ago, North America’s horses were gone, and for thousands of years, the Mojave Desert knew horses only as fossils hidden in stone.2

But Now Am Found

Fortunately, the story of our friend Rupert the lost horse has a happy ending. Hikers searched. Friends shared updates. Rangers kept watch. After a day or so he was found halfway up a mountain about three miles from his last location on Stirrup Tank Road.3

“I once was lost, but now am found.”4 Horses have been lost here—extinct, stolen, wandering, and escaped. Some were found again. But others live on only in stone, stories, and place names like Jackass Trail on the western edge of Twentynine Palms, the Burro Trail, and the Lost Horse Mine.

The Year of the Horse asks us to reckon with motion and meaning, ignoring the temptation to bolt—and, if we do, engage with the harder work of returning. The Horse honors courage and vitality, but also reminds us how easily momentum becomes frenzy. As we step into this new cycle, may we move boldly without abandoning caution, and may we watch for one another on the trail. For in a place shaped by loss, finding becomes its own quiet act of (amazing) grace.

Thanks to our new paid subscribers, we are at $8500 in subscriptions, just $1500 short of our $10,000 goal. Upgrade your subscription from free to paid today for just $50 per year or $5 per month.

Are you able to give more than $100? Donate via Paypal!

Leave your thoughts in the comments below. Please note that we do not allow anonymous comments. Please be sure your first and last name is on your profile prior to commenting. Anonymous comments will be deleted.

Feel free to share this article!

Paleontologist Dr. Stephen Brusatte has written a terrific book on mammal evolution: The Rise and Reign of the Mammals: A New History, from the Shadow of the Dinosaurs to Us (2022).

There’s some question about whether Rupert should have been in the Stirrup Tank area in the first place. Here is JOTR’s page on where horses may be ridden in the park.

You recognize, of course, the lines from “Amazing Grace.”

Beautiful article Kat. Lovely metaphors. Wonderful history. -- Diana Manchester